Your Thirst Is Mine, My Water Is Yours

...or how I learned to stop caring and share my water.

On the 29th of Simmun Ut, I arrive at the oasis-hamlet, the village Joppa, on the far rim of the Great Salt Desert, Moghra'yi. The air is humid– watervine farmers tend to their viridian plants, their homes mere huts of brinestalk and rock salt. On the horizon, Qud's jungles strangle chrome steeples and rusted archways. Beyond, the fabled Spindle stretches upward, piercing the cloud-ribboned sky. I embark on the Caves of Qud.(*)

Who I am is of lesser consequence, as my frail body won't even make it far, with nary a girshling corpse, the only cadaver mine own, to be stoned by those noble baboons that call the red stone their home. I go to them soon, to find stairs down to the Caves of Qud, on the request of a farmer, who bade me: "Our pools bathe with this red rust, see? This is stone from Red Rock: go there, find the creatures eating our vine, deep underground. Bring back one of their corpses."

His name? Mehmet. He has a crooked back, wind-bent by age, a salt-crusted brow, his scarred knuckles firmly, comfortably, hold a trusty vinereaper. He is well-loved by his neighbors, but hated by the village of Tanna, as he reprogrammed their favorite robot. He is loathed by the mopango, as one day a young Mehmet, famished from tending the vine, ate all of their fruit.

When I arrived in Joppa, he was the first to greet me: "A waterhand? Aye. Live and drink, traveller." Live and drink. In the lands of Qud, fresh water is currency. The rivers and lakes are diluted with salt, so drinking water is scarce and precious. Pity, all creatures need a drink. Sharing water is a holy ritual, of bonding and family-making. I hold out my waterskin and offer him a dram, crowning him my water-brother. I utter the words I would end up repeating over a hundred times, over the course of a hundred different lives:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

I would like to make an amendment to my 2024 Top 10 Games List. Sunset Visitor's 1000xResist still holds the championship belt as 2024 GOTY. I would throw Thank Goodness You're Here! out of the list and into an honorable mention, crippled by the hyper-specificity of its taste on my palate. I would then place Freehold Games' Caves of Qud on the roundup, with high praise.

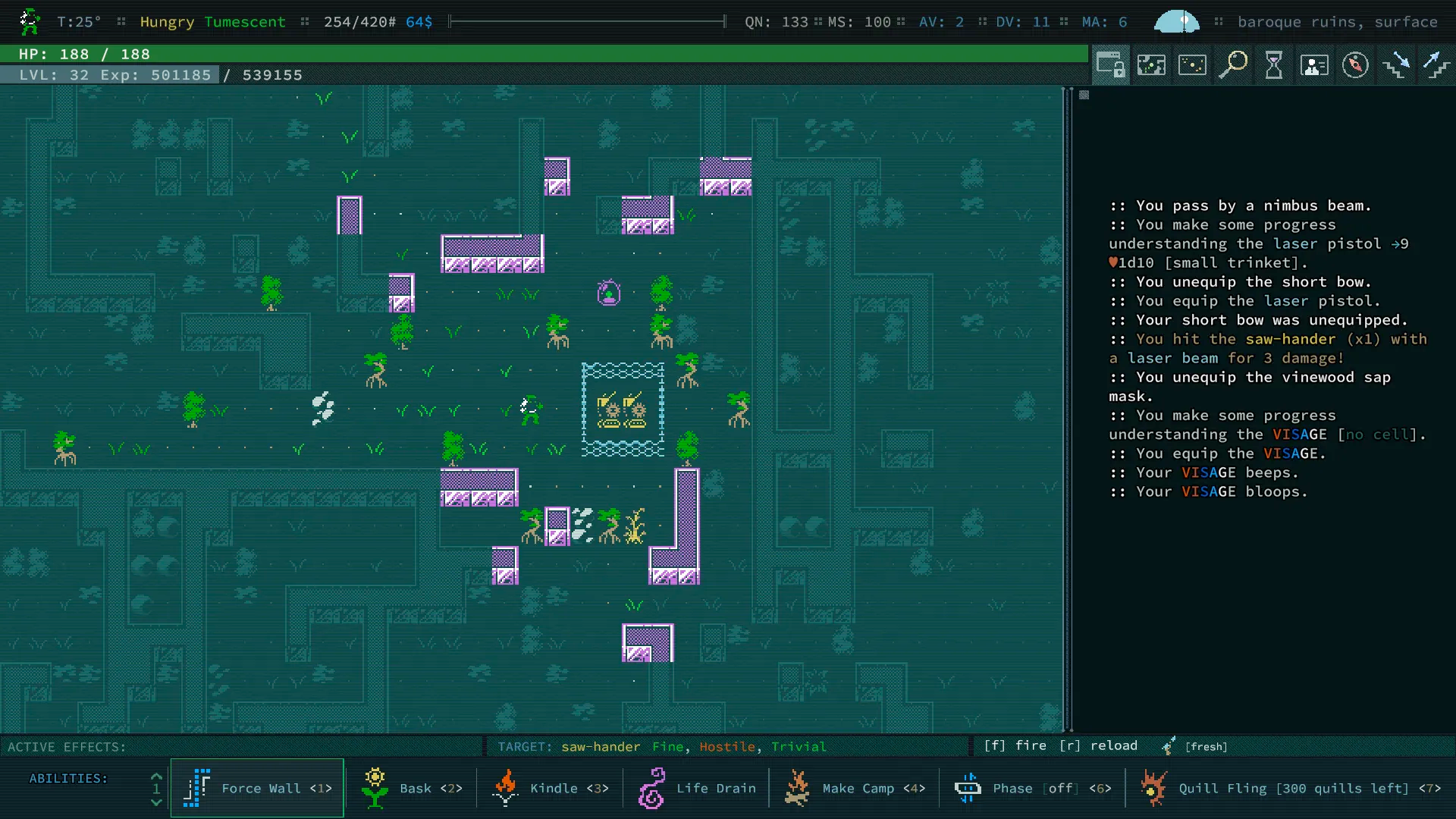

Introducing Caves of Qud comes with a side of word salad, that reads off like degenerate utterances or Dadaist scrambles. It's a turn-based, old-school, rogue-like/RPG set in a post-apocalyptic/fantasy/sci-fi setting, in a world where the histories, locations and relations between the myriads of factions are procedurally/randomly generated.

It is a game highly praised for its gargantuan mechanical depth and nonsensical scenarios that spawn out of a Random Number Generator. I've smoked hookah with baboons, proselytized so hard I convinced a phosphorescent cat to follow me into battle, and sent snapjaws tumbling through space-time vortexes. I once found a strange artifact, a mysterious husk of metal and tubes. Upon my character conducting a closer examination, the odd trinket revealed itself as nothing else but a regular folding chair.

Caves of Qud is more than a mere anecdote generator–it is a game in which the players themselves construct the emergent narrative. I believe it was the famous Slavic philosopher, Warlockracy, who once said (and I am paraphrasing here) that there are two different types of storytelling in Role-Playing Games:

*There's RPGs in which the story and narrative happen around the player, and can even center the player, but can only be superficially manipulated via dialogue choices and actions. These are your Bioware or Bethesda RPGs. Even, God forgive me, an all-time favorite of mine, Fallout: New Vegas, falls into this category. It's not at all a negative statement – it serves as a valid method of storytelling, where the creators retain control of the story, while still leaving some semblance of agency for the player.

*Then, there's the RPGs in which YOU are the story. These would be your Disco Elysiums or Baldur's Gate 3s, and of course, Caves of Qud.

While all these games have an over-arching plotline, one that was meticulously constructed by its makers, the most memorable moments are those in which I was able to regale my own tales via my interactions with the games' worlds. Due to mechanical complexity, random dice rolls or insane-o builds, they offer a much deeper way of engaging with virtual worlds – serve as powerful ways to connect our interior lives to the realm of gaming and concoct our own personal narratives from them.

The most memorable moments in Disco Elysium, for me, were the sillier aspects, like dying of a heart attack from sitting too long in an uncomfortable chair. It was that or the emotional hard-hitters – the moments that made me empathize with a virtual cop. For Baldur's Gate 3, a game so rich with lore and characters, my best remembrances are the moments I creatively turned the tables in combat scenarios, what with a little bit of cheese or a series of exploding barrels. That and the confidence that, no matter what, the game was going to respect my choices and exploits, move on with the plot, while keeping track of a laundry-list of variables.

Caves of Qud is the ultimate representation of deep mechanical interactivity. After I got through the steep learning curve and the inaccessibility of its UI, I encountered one of the most creative and profound games in recent memory. An anthropological wonder, that made me feel personally connected to its rough environments and tough-as-nails gameplay. Not since first playing Morrowind, did I find wonder in such a strange, alien world

Caves of Qud is a treasure I found when I needed it the most – a shimmer of hope amidst a living hellscape, representative in both our reality and the post-apocalyptia of the game's setting. What kickstarted my obsession was a simple line of dialogue, which I repeated, and will continue to repeat, ad nauseam:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

Identity is a core theme in Caves of Qud. Who you are matters, lore-wise and mechanically speaking. Be you mutated human or true kin, your starting character and village affect your interactions with the world at large. The character creator is complex – an overwhelming smorgasbord of customization that feeds into roleplaying possibilities. A four-legged greybeard is hated by the Templars of Putus, a Child of the Hearth can rebuke robots. Spawning in the salt dunes teaches your character the art of fasting, as food is rare and nothing grows in the saline soil, the desert canyons net you positive rep with the reptiles that call the arid landscape their home.

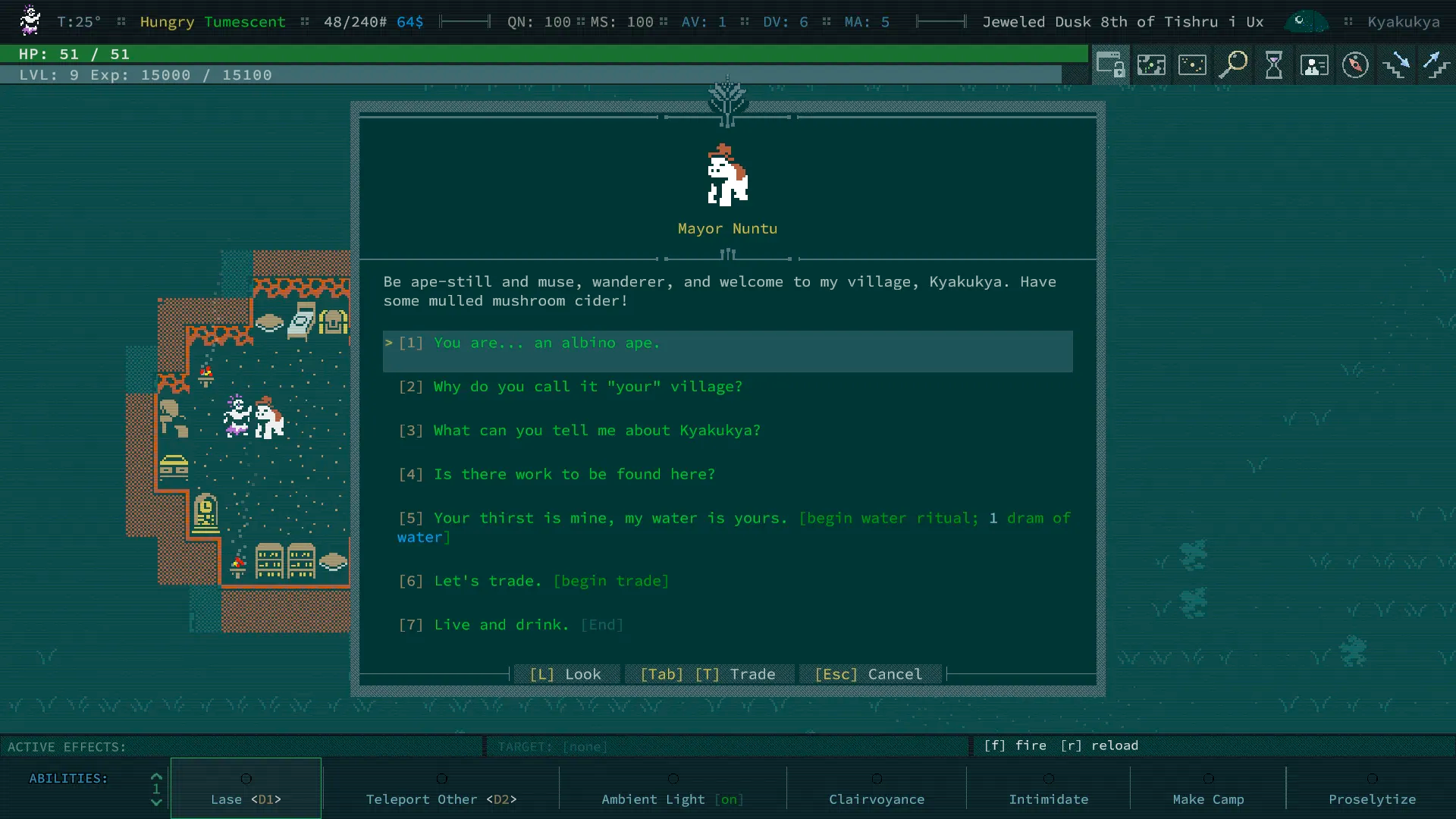

Whichever village you spawn in, access to the water ritual is immediate. Walk up to a legendary or important character with a dram of their preferred liquid and recite the sacred words.

The water ritual fundamentally alters your relationship with the world around you. You will be adored by those who love your water-sib and despised by those that feel negatively about them. Since water is such a precious commodity, the water ritual transforms a simple act of kindness into a praxis with deep societal consequences. It is a sacred act, spiritual in a way, with its forming and strengthening of bonds across cultures and species. The water bond is a connection that, when severed, turns you into a pariah – everyone will dislike you if you break this holy pact. It would be akin to breaking xenia in the times of the Ancient Greeks, the doctrine of hospitality that was also seen as a sort of "ritualized friendship", rooted in generosity and reciprocity, punishable by the Gods themselves.

As a cultural object, the water ritual is the only common law and courtesy in the harsh lands of Qud – it is a custom that transcends even identity. If not outright hostile, you can share your water with any creature of note – wise leaders of mutated men, talking fire-breathing alligators, and mighty warriors who've braved the jungles. Once, I even shared my waterskin with a legendary apple farmer, a title I assume she won through decades of survival and her impressive resume at the local orchard.

Once you share your water and acquire reputation, these points can then be spent on various benefits: learning the recipe of the local traditional dish, the location of a ruin with possible riches, and, most pertinent to this text, asking your newfound confidant to follow you into the battle. It is not a simple trade – water for goods, info or companionship – the water ritual is not superficially transactional. It remains sanctified.

As an old-school roguelike, Caves of Qud is a difficult game. Its combat is an ever-increasing gauntlet of skill-checks and "what the fuck killed me"s. Dying, at least in its classic mode, is harsh and punishing, with no re-dos, restarts or revives. Dozens of hours can be gone to the wind with a single mistake. Having even a single follower can significantly turn the ever-changing scales of battle to your favor.

My first followers were not relationships forged with chains of liquid, but coerced companionship. Opponents I dominated with my mind, innocent villagers I convinced via zealous sermons, animals I forced to adore me.

After my first few runs, I'd learned how to deal with the simians at Red Rock. I waltzed into the the monkey lair a Syzygyrior, haling from Ekuemekiyy; The Toxic Arboreta; The Holy City. I held out my dagger and axe, steeling myself for an attack...and was surprised to not have a hail of stones thrown my way. The simians were peaceful, for once. Turns out my water-sister Yrame, Warden of Joppa, had once saved a baby monkey from drowning in a salty river, earning the species' eternal gratitude. Conversations were less stimulating with them, and they had nothing to trade, but I loved being amongst the baboons. Not enjoying the company of chimps is indicative of some moral or personal failing, in my opinion.

I met a hulking ape with thick, golden fur, bigger and stronger than his comrades. Some wheels in my head started turning and I pulled out my pack. I grabbed a glass tube, filled with a bubbly pink liquid, a needle sticking out one end. I asked him if he would like to live deliciously, not going a single day without his wants or needs filled, with a single, undying, purpose. All he needed to do to satisfy that urge, was let me stick him with my love injector. I assume he took this as some sort of coital invitation, so he declined the impromptu vaccination. I furiously grabbed the cylinder, sharp end gleaming in the sun, and I forcibly stabbed the hulking baboon, injecting him with the love serum.

The liquid makes you swoon for half a day. You will fall in love with the first thing you see. When the ape opened his lids, he saw me with amorous eyes. At that moment, the ape lost its identity. I imagine memories of days basking in the sun, nights under the cloudy sky, lazing on the wet grass amongst his simian friends, and a whole lot of swallowed bananas. In a moment, all gone. What followed was a bloodbath. Having witnessed me attack one of their own, the rest of the troop started circling me, with the occasional stone thrown my way. I didn't expect my newfound, infatuated ape-follower to charge at them, and slaughter his monkey-brothers. The stones at Red Rock were made redder that day.

Caves of Qud's deep mechanical ingenuity is representative in moments like these. The game's tutorial teaches you the basics: how to move, how to fight, you must drink, you must eat, but otherwise leaves you to figure things out on your own. It wasn't just that I engaged in a simple process of mechanical gameplay: the love injector clearly described its effect in the inventory menu, but it was I who had to figure out that, if the ape refused the injection, I would have to equip it as a weapon and forcibly attack him. This then cascaded into a serious of events: a new follower and a massacre.

The ape and I saw few battles. We fought through the entirety of the caves below Red Rock, strata deep, brought back Mehmet his arachnid corpse at Joppa, gave the local tinkerer Argyve his artifacts, recovered from the depths. Moved by our labor, he begs us to go the rust wells east of the village, to fetch him two-hundred feet of copper wire.

It was beneath the well, fetching him his blasted strands, that my hulking baboon companion bit the dust. At first I was proud of my ingenuity, that I was able to put two and two together and command a creature to love me through a game's mechanics. The guilt frayed my soul. The massacre I unwillingly unleashed, the betrayal of monkey-bonds cemented in liquid bonds – not a water-bond, but a blood-brotherhood of apes I so willingly destroyed for my own selfish desire. I even felt his love was a facade, mere chemical persuasion; this unnamed ape loved me, unwillingly. Alas, it was only after he perished did I realize I loved him too. He had helped me make it farther into the game than my previous failed runs.

I bathed his corpse and uttered the words of the rite:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

Live and drink, noble creature. If fate were different, I would've made you a proper water-brother.

In my grief, I fell to the creatures that haunted the well, and went right back to the start with a whole new character.

Classic mode is the best way of engaging with the game. It's the true roguelike experience Caves of Qud envisions. Play with a random character each time, as I did, for further difficulty, and recreation of the genetic lottery we are susceptible to pre-birth. The permanence of your decisions and the fear of losing everything almost necessitates a slower pace – more pauses along your journey. It allows not just for tactical thinking, but at fomenting in the player a certain attention to detail, lore and surroundings.

It's through deliberate interaction with the world that Caves of Qud gets you to engage with its possibilities. The power of imagination remains the strongest current of indie gaming. The game's lo-fi graphical design belies a varied, multi-cultural world. It forced me to use my own head to abstract the fascinating scenarios. A few pixels representing sand, a few static images move sideways into my own pixelated avatar to represent combat. But in my head, a detailed battle amongst the salty sands, fending back Issachari raiders donning rifles and long brown cloaks.

It might surprise readers that have not played this game to know that I have abstracted the scenarios I experienced in the game into this text. My first encounter with Mehmet was just a still image of yellow pixels and a list of dialogue choices. Hanging out with monkeys was just my character wandering around near their habitat. But in my head: perfect, picturesque representations of fantastic scenarios fueled by the the GPU inside my own mind.

In a way, the most impressive aspect of Caves of Qud is its depth despite its lo-fi attitude. Indie games often contain the more unique and original game design philosophies at the cost of scope and graphical fidelity. CoQ teaches us we do not need to sacrifice immensity. We can represent it, mold it, play with it.

My favorite character was a four-armed marauder. He had learned the arts of butchery from his starting tribe. He held an axe on each hand and a flurry of blows destroyed anything that reached his personal space. He was cunning and reveled in the carnage – all corpses were succinctly shaved down and amateurishly cut for meat to feast.

In my head, a bloodthirsty, hulking, demon of a mutant, always soaked in the red vein-liquid – in the game, but a static white image of a heavily-pixelated mutant. The reason I was so favorable to such a violent power-fantasy, was mostly due to the fact I rarely get the chance to roleplay anything like that archetype. I have a curse in which I can't create wacky, zany or evil characters in RPGs, instead reverting back to a classic goody-two-shoes with a knack for asking too many questions.

Despite my roleplay of a violent cannibal, I would restrain my thirst for conflict whenever I ventured into a new village. No matter what character I play, I remain enshrouded by the holy water ritual. I walk up to the leader of a peaceful village of mosuqitoes, nestled within the building-corpses of the old world and I offer him my waterskin.

I shared my water plenty, but found no opportunity for others to join me. I learned delicate meat dishes, even mastered the art of fasting for when the guts stopped flowing, but they never would. I kept carving my way through the Caves of Qud. I tasted victory in the entrails of my foes.

I ventured into a ruin and tore its robotic defenders apart. I found within a mechanical wonder – a backpack that added two more robotic arms to make me an insect-monster of an axeman. Two more axes to each cybernetic appendage and the brutality continued.

I annihilated any foe that came within axe-range in a tornado-flurry of bladed swipes. I felt unstoppable. Hubris is the biggest killer in the lands of Qud. Barely a few minutes after acquiring my destined mechanical arms, I was overwhelmed by a group of goatfolk in the jungle. I refused to run away, and died in reciprocated glory – with my guts being devoured by my worthy opponents.

Even then, with my innards forcibly removed from my body, I wished I could have made these monsters kin, and share with them, willingly, my own blood, and recite the words:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

My hyperfixation with the water ritual stems from the core of my ethical and political beliefs. It is reminiscent of the mutual aid efforts I've been engaged in for years. I've made "subtle" quips in the past about how I am fully convinced we're living in a techno-capitalist dystopia – a pseudo-fascist hellscape. Politicians and governments will not save us – we have to depend on and take care of each other to survive. Ergo, it is important to share your water and food with your neighbors.

While mutual aid has political undertones that the water ritual lacks, they both engage in the process of creating, fostering and strengthening community. Sharing necessities with needy neighbors and friends strengthens your bond with those in proximity to you, sharing your water in CoQ allows for companionship. Ergo, no matter who I played, I feverishly shared my water with anyone I could. I wished to share my water with creatures I couldn't even start the water ritual with. To the monkey and the goatfolk, I wanted to utter the words of the ritual.

It is no surprise then, that my best run was with a character that charismatically led his own small army. In a way, more than an armed group – a troupe of water-siblings braving the wilds of Qud. I met all of them through skillful diplomacy and over-use of the water ritual.

My group, at its biggest, was composed of:

*around five to seven screaming Machinist zealots

*Two repurposed scavenging robots

*A wise, fire-breathing crocodile

*Mehmet, the vine-farmer himself

*A pink Dragonfly

*And, my personal favorite, the legendary glowcrow, CA-ca-caw-caaaaa-caaaw

The wilds were less dangerous, Red Rock was a breeze, the Salt Wells a pleasant jaunt. But the AI is, to be frank, a bit wonky. There's some issues with pathfinding, what with followers getting stuck in the scenery. They would often not attack hostiles unless I explicitly direct them, but I'd rather chalk that up to the faction system at play rather than an inherent flaw of the game.

Regardless, the size of my group offered a sort of safety net. I could just sit and wait and let them deal with the monsters and creatures. Don't misunderstand me: I would often get personally involved in battle, charge at the enemies with shield and mace, spill blood alongside my brothers and sisters.

I was finally able to give Argyve his wire – eureka, his machine-conduit, finally finished, intersected a strange transmission, a repeating signal that confounded the tinkerer. He asked we go to the Grit Gate, to visit his friends, the Barathrumites, to make sense of the static noise.

All my best runs ended there, my previous one right outside the lair of the sentient tech-bears, gunned down by one of their sentry robots. With my group, I had no issue or difficulty getting to the Grit Gate, but a colossal accident happened on the way to Golgotha. See: the Barathrumites are untrustworthy souls, so they requested I bring back a repaired droid from the great cloaca.

While exploring the arid landscape of Qud, I found a laser rifle that could be charged with energy cells. Excellent: my character was a powerhouse with blunt weapons and rifles. The tight corridors and narrow hallways posed a challenge with shooting. Friendly fire is on, and I found out the hard way.

I accidentally unloaded a laser-powered projectile to the back of CA-ca-caw-caaaaa-caaaw's head, beloved elder of glowing birds. The battle was paused so windows could inform me I committed the most grievous sin – I had broken the water ritual.

I had, by accident, killed someone I shared water with. The people that hated CA-ca-caw-caaaaa-caaaw already despised me, but now the bird's confidants and friends hated me too.

The water ritual is almost magical – everyone immediately knows your stance and reputation. The breaking of holy bonds was a portend of doom. A couple Machinist cultists had already fallen, like so many souls before, and the rest of my followers were slowly dying to the ensuing battles. During a particularly fierce battle, Mehmet died, the fire-crocodile perished, and the pink dragonfly flapped its wings one final time. I entered Golgotha with my sludge-stained scavenging robots, and got summarily annihilated by the opposition there.

I believe a part of my character was depressed. Breaking the water ritual, even by accident, is akin to betraying your kin and community. I had build an identity as a leader of mutants – a friendly sort who passed the waterskin around to his friends, nestled by a campfire. This part of myself died the moment the glowcrow's brain was summarily melted by a laser. I think a part of me, yet again, gave up.

This was my best run yet, and I barely made it to Golgotha. Too late in the game to show my cards: I have yet to beat Caves of Qud.

Yet, I shakily hover my mouse over the "New Game" button and start again, in classic mode, with a new character. If there's lessons to be taken from my anecdotes, is to know when to fold. Sure, I surrendered myself to defeat, but I always tried again, always spurred by the beauty of the words:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

I love the poeticism that is implicit in such a statement. It is an acknowledgement that, even in post-apocalyptia, when someone suffers, we all suffer. That our measure as a society is only as good as who has the toughest material reality. That someone's thirst isn't just their own, it's our communal thirst as well. And if your thirst is mine, then the only ethical thing to do, is acknowledge my water is also yours. It is one of the most empathetic actions I've ever engaged with in the realm of gaming.

I know a lot of people are suffering right now. God knows 2025 has already been rough for my personal life. But if there's one lesson to learn from Caves of Qud, is not that you should take someone's suffering as your own, and fall deeper into despair. Instead, in the acknowledgement that if one of us suffers we all suffer, we could open our hearts and assist those who truly need it.

I urge you, no matter who you are, to share a drink with a stranger, preferably someone who really needs one. You don't have to recite the words in-person, but you should at least repeat to yourself, inside your own head, the sacred script of the water ritual:

Your thirst is mine, my water is yours.

Please everyone: be good people, and take care of yourself and each other.

(*) It would be ethical of me to disclose, that this paragraph is partially taken from the introductory message of Caves of Qud. I paraphrased the sentences to fit certain stylistic choices, but much of this is not my original writing.