Fighting Like A Dragon

Buff Japanese Men Rock and other lessons I learned along the way.

—Spoiler Warnings for Yakuza 0 and Yakuza 4. Minor spoilers for the entire Yakuza/Like a Dragon franchise—

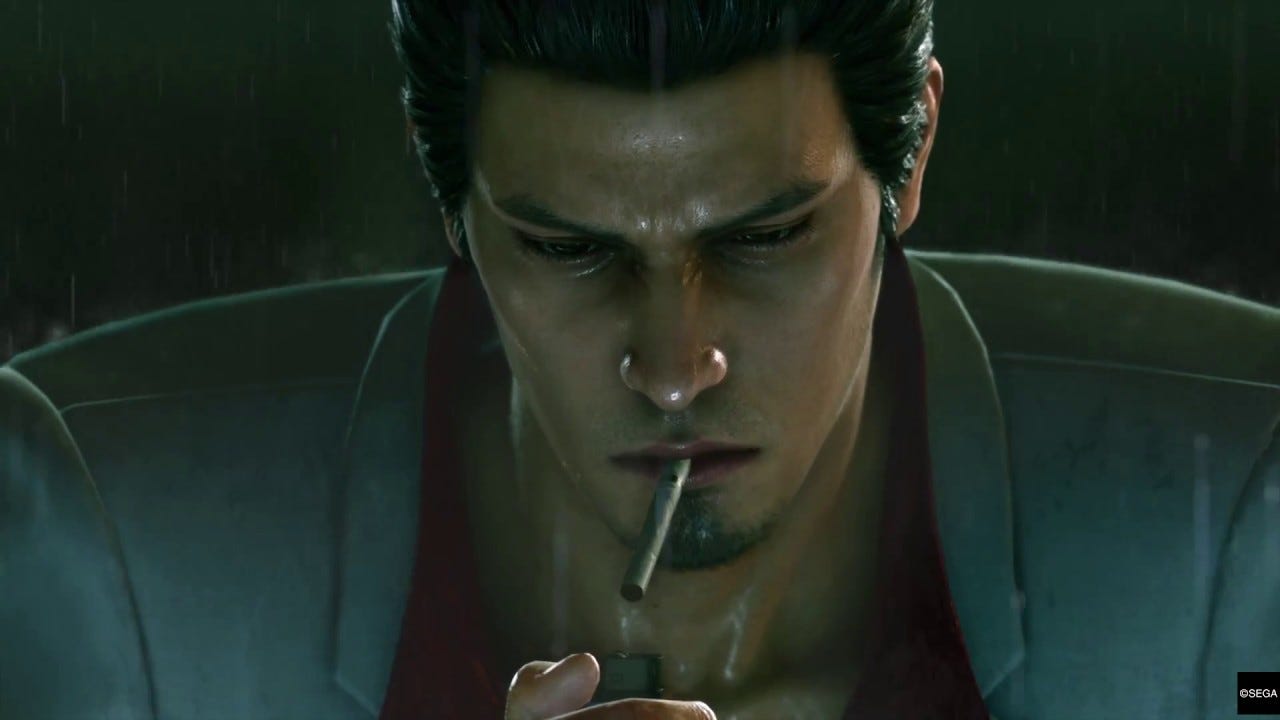

I fucking love the Yakuza series. This is the understatement of the century, as I don’t think I can properly express my appreciation for the Sega-published beat-em-ups in a single sentence. During a blazing summer heatwave in 2020, while living in a rat-infested, poorly-insulated warehouse, I bought and downloaded Yakuza 0, on a whim. I was expecting mindless entertainment, and, in a way, I received exactly what I paid for…but ended up getting so much more...

What hooked me to the series was a moment right at the beginning of 0, where series protagonist, Kazuma Kiryu, follows his lifelong friend and fellow gangster, Akira Nishikiyama, to a small bar. It is here where I was introduced to the first of many minigames: karaoke. Pick a song, and match the on-screen notes to button presses on your controller, a simple yet effective rhythm game. I chose the more energetic of the two tracks, “Judgement”. A classic 80’s rock guitar riff starts blasting out of my speakers. As I am slamming my fingers in perfect sync with the notes flying across the TV, the screen suddenly goes white, and a short cinematic plays in the background. This was supposed to be a game about angry, hardened criminals, but here they are, on a stage built by imagination, donning leather jackets and red puff pants, cheesily singing about “breaking the world” and “tearing apart tenderness”. It immediately endeared me to these rascals.

From that moment on, my psyche was irreversibly changed. I have gone on to play every single Yakuza game released in the West, including its spin-offs. I didn’t just play them: I marathoned them. I played nothing but Yakuza for half a year. I fell deeply into a world of neon lights, buff Japanese men, over-the-top action…and ended up learning some important life lessons along the way.

What draws me to write about this series with such fervor, is the fact that Yakuza (or Like a Dragon, as it is currently rebranded) accomplishes tonal dissonance like no other. It is stock full of dichotomies and contradictions co-existing and clashing with stunningly positive results. On one hand, you have a serious, if overly melodramatic, crime drama rife with conspiracy, corruption and murder. On the other, you have a balls-to-the-wall explosion of violence, action and goofiness. You go from investigating political schemes in one moment, to battling a monkey operating a backhoe in the next.

It’s able to succeed in such a feat, because instead of creating these vast open worlds for you to get lost in, Like a Dragon offers these minuscule maps packed to the brim with side content and “substories”: self-contained side quests where the protags show off their personalities and helpful attitudes. Kamurocho, based on Tokyo’s real-life red light district, Kabukicho, is the main setting of the games, although the series has taken place in many other Japanese locales, albeit on a smaller scale. It is in these contained spaces, where you navigate through the main story, explore, eat in restaurants, knock back drinks in bars, play Sega classics in the arcade, partake in a bit of bowling, darts, cabaret clubs and…pocket circuit racing? A battle arena full of half-naked wrestling women?! Is…is Kiryu punching a shark!?! All of this is just to say: the limited geography of these games makes it difficult for you not to run into anything silly.

Even when trying to be serious, Yakuza games can’t keep a straight face. The twists and turns of its plots seem to be pulled straight out of a soap opera. Secret parents, faked deaths, hidden identities, twin siblings, extensive plastic surgery to alter one’s appearance: these are all scenarios dispersed across the Like a Dragon entries. They’re not tongue-in-cheek. These are serious plots and characters react with gravitas to the sudden revelations. But…they’re campy. I couldn’t take any of it seriously.

In Yakuza 4 one of the main characters, Taiga Saejima, is exonerated from a massacre he committed. You can clearly see him in a cutscene, donning a revolver in each hand, another gripped tightly in his teeth, more tucked underneath his jacket and belt, stomping into a ramen shop full of high-ranking rival Yakuza. He “fatally” shoots 18 men. It is later revealed that the guns were loaded with rubber bullets, without his knowledge, all part of this grand conspiracy devised by the game’s villains. 18 men got shot with non-lethal ammo, not-a-one gave signs of life, making Saejima think he killed them, only for them to be murdered by some other dude shortly after. I felt my intelligence was insulted. This is not the zinger the game thinks it is. Why all these extra steps for a “gotcha” moment? And yet, just like the karaoke scene, I was mystified. Instead of detaching me from the game, it pulled me closer, tighter into the story. I was invested. Yakuza 4 is now forever etched in my brain as “that one game with the rubber bullets plot twist”. Many of the series twists follow equally convoluted plot threads and entanglements.

If you are willing to invest in the series, roll with the punches and accept the melodrama, you will be rewarded with emotionally effective scenes. I am not ashamed to admit Yakuza has made me cry. The death of certain characters floored me. It’s heartbreaking to see a sensitive, well-meaning character like Ichiban cry. It’s tough watching Kiryu suffer so much, getting pulled into the devious machinations of gangs, the police, and, oh, the fucking government, when I know deep down he just wants to run his orphanage in peace. The sadness is then sharply cut by some humorous scene, crashing its way in. These tonal inconsistencies throughout the series, for the first time in my gaming experience, served to enhance my enjoyment, rather than detract from it.

The tonal whiplash common to the series is present in the main gameplay loop: beating the fuck out of people. Like a Dragon engages in what I refer to as “wholesome ultra-violence”, an oxymoronic term that accurately represents the combat.

As you chain together light attacks, heavy attacks, grabs, blocks and taunts, a secondary meter underneath your health bar starts rising, appropriately called “Heat”. When your “Heat” is sufficiently filled, you can execute some stylish finishers with a single button. These are context-sensitive. If near a pole, you launch an enemy groin first into it. Next to a wall? Introduce his face to the bricks. You can suplex people into guardrails, breaking their backs. Grab items and weapons and use them for your “Heat Actions”. Stab…shoot…or simply smash a bicycle on a downed combatant. Saejima even possesses a heat action where he rolls his opponent into a snowman (requiring a carrot in your inventory for proper execution). The wackiness is inescapable.

Excessive as they may be, these encounters are by and large non-lethal. Even if you break some random thug’s neck, they stand up after combat is done, at times no worse for wear, apologetic and clutching their stomachs. The logic of the Yakuza universe is that actions that would normally cripple or kill have little to no lasting consequence. A bullet is only deadly if the plot demands it, and it’s never fired by a protagonist. There is no killing…in a game about the Japanese underworld…

Series protagonists are rarely the aggressors in random enemy encounters. They are acting in self-defense, or protecting those being harassed and taken advantage of. They’re all warmhearted people. They don’t want to cause harm to innocents. A lot of the minor enemy goombas even end up changing their ways, finding resolution to comedic misunderstandings or problems thanks to their run-ins with the protags. Even though, moments ago, the same individual giving them life advice was beating their head in with a traffic cone.

It is in how violence is represented in Like a Dragon that we observe the greatest tragedy and contradiction of the series: Yakuza is full of determined, driven, broken men, who don’t know how to resolve conflict without resorting to fisticuffs. Yet, Yakuza protagonists, specifically Kiryu and Ichiban, are the best representation of positive masculinity in gaming.

Despite being bulking meatheads with a propensity for violence, their faces adorned with permanent scowls, Yakuza protagonists live under strict codes of honor and justice. In no series entry can you go around beating random people up. No one you control would ever dream of fighting someone that doesn’t deserve it. Kiryu makes for a horrible criminal, but a wonderful human being. He is critical of the Tojo Clan’s propensity for extorting money off of regular civilians and continues to live his life under strict moral guidelines, continuously coming to blows with his former clan as a result. Kiryu is a defender of the weak. He doesn't hit women, he’s a trans ally. He is compassionate, kind and always willing to lend a listening ear, to resolve random people’s problems, mundane or ridiculous as they may be.

Ichiban Kasuga, the protagonist of Yakuza: Like A Dragon (aka Yakuza 7, as if the series rebrand wasn’t confusing enough…) is bombastic and emotional, a stark contrast from the serious and stoic Kiryu. Yet, they share the same values and beliefs. Obsessed with Dragon Quest, he sees himself as the hero of his own RPG. He rushes headfirst into danger with reckless abandon to protect his friends and loved ones. He and Kiryu would do anything for those they love.

Through plots and deception, lies and betrayals, trials and tribulations, these righteous men prevail. And what is a righteous man? According to Yakuza, it’s someone who uses his strength for good, to become a champion for the oppressed. A righteous man takes accountability for his actions and works hard to make amends for his mistakes. A real man oughta be a little stupid, yet never for the benefit of evil men. These heroes of the Yakuza world didn’t become legends by strength alone, but by learning when to kick back, relax, enjoy a drink with friends, sing some karaoke or eat ten beef bowls in a row. They know how to live life to the fullest, with conviction. We could all learn something from these fictional Japanese criminals.